Interview with ceramic artist Shingo Takeuchi (Seto, Aichi Prefecture)

Share

On a sunny day when scale clouds covered the sky like lace, I visited ceramic artist Takeuchi Shingo in Seto City, Aichi Prefecture.

The journey to becoming a potter

I was born and raised in Seto.

At that time, the area was lined with pottery factories and my childhood playground was around there.

It's hard to imagine now, but the unfired works were simply dumped in rivers and other places, and I used to play around by throwing them (laughs). There were a lot of heavy oil kilns for mass production, and the chimneys went through the ground, and when the kilns were fired, the ground got hot. So I brought some sweet potatoes, buried them in the ground, and roasted them (laughs).

Because of the kind of childhood I had, I had no resistance to soil whatsoever.

After working as a salaryman for three years, I enrolled in the Aichi Prefectural Ceramics Training School, where I studied pottery for free for one year while receiving extended unemployment insurance benefits. Around 1979, during the period of rapid economic growth, the phrase "quitting the job" was in vogue. There were many students in my class who were enthusiastic about making pottery, and by the time I graduated, I had decided to make a living as a potter.

After graduating, I apprenticed at two potteries that used wood-fired kilns and gas kilns for a total of three years to learn the trade. Then I became independent. In my second year, I started receiving work from all over the country, and I have been fortunate to have received orders from about 40 stores and have exhibited my work in solo and group exhibitions both in Japan and abroad, and this year marks my 40th year as an independent potter.

Please tell us about the process of making your works.

He puts his own blend of red clay into a kneading machine, then piles up the clay in thin strings to form the shape. In other words, he does not use a potter's wheel. He makes a small model out of a lump of clay and works while looking at it. This is a technique called "string making," and it takes about 30 minutes for a small piece, and about an hour for a slightly larger flowerpot, and he piles up the clay while imagining the shape he will have after it is completed.

When carving, holes may appear on the edges, so we stack the pieces as evenly as possible while considering the finished shape (it would be problematic if the thick parts took a long time to dry and the thin parts dried quickly).

It depends on the season, but we usually start scraping the snow the day after it is piled up.

Please tell us about your distinctive "shavings"

It generally takes me 2-3 days to carve each piece, mainly using saw blades, saform, and boxwood.

The soft exterior is carved into the hard interior. As the thickness is further carved, the tools are changed, and the carving method is changed depending on the clay and the shape. Every day, the carving and drying is repeated to create sharp edges, and the piece is nearing completion.

Once you've finished scraping, leave it to dry completely.

No stove is used for drying, but towels or, depending on the piece, blankets are used to cover the pieces and allow them to dry naturally over a long period of time. After drying, the pieces are bisque fired at around 800℃.

After bisque firing, a clay-like coating containing a lot of iron is applied to the entire piece and then quickly wiped off. When wiped off, the iron coating remains on the edges, creating a dark line-like design when finished.

After that, a non-melting glaze (a mixture of alumina and wood ash) is brushed on, and the piece is ready for firing.

Please tell me about the final firing and cooling reduction.

I use a gas oven.

The final firing involves reducing the metal at around 950℃, then raising the temperature to 1250℃.

It is common to heat the furnace to the temperature at which the glaze melts and the clay hardens, and then allow it to cool naturally, but doing so quickly causes the inside of the furnace to become oxidized, and as this oxidizes the piece turns brown.

In my case, I use this oxidation at a temporary temperature range to equalize the temperature inside the kiln.

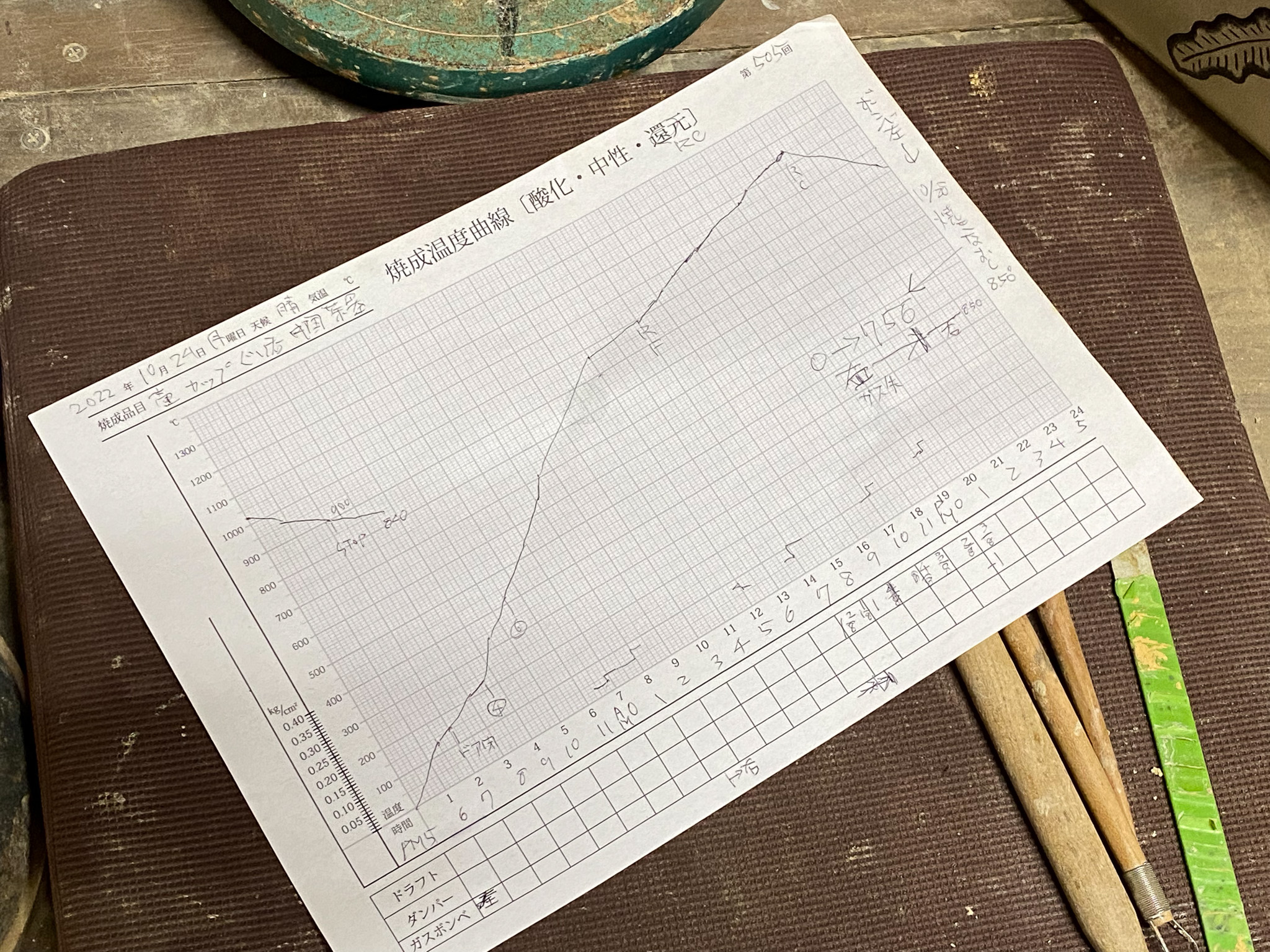

When lowering the temperature, gas is turned on and the kiln is cooled down to around 900°C while in reduction mode. This is called "cooling reduction". By continuing the reduction process while cooling, the kiln takes on a concrete-like grey or black appearance. Once it reaches 900°C, the gas is turned off and the kiln is allowed to cool naturally. As a gas kiln is used, it does not have the microcomputer function of an electric kiln, so the gas pressure and temperature must be controlled by drawing diagrams yourself during the final firing.

Although this varies depending on the clay used and the piece placed inside, the kiln is opened and the pieces are removed at approximately 150℃ to 100℃.

Once removed, the piece is beige in color as shown on the right in the photo below. When a wire brush is used to peel off the insoluble glaze while running water over it, the resulting piece is a concrete-like gray or blackish fired piece, as shown on the left.

OMBLE : Thank you very much for reading to the end.

Shingo Takeuchi is a world-famous potter who creates pottery in Seto.

As reported above, the finished piece, which took a lot of time and effort from shaping to drying, scraping and firing, is a work of art that truly expresses liberating freedom.

Rugged yet sharp, I'm sure this is the perfect flowerpot to display your favorite plants.